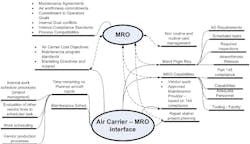

Last month I spoke about MROs preparing for the air carrier interface. In this segment I’ll look at the air carrier side of this complex relationship. Air carriers are accountable for the performance of contractors who perform maintenance on their aircraft. The lens most used by air carriers is the MRO’s compliance with Part 145. Audit criteria used by the operator’s quality organization are aimed at assuring the MRO is in compliance with its standards.

Here lies a key difference between each organization. Air carriers are really good at being air carriers. They are operating to their set of rules; a highly structured organization intended to provide the safest travel experience possible to the public. However the cost of maintaining that infrastructure is pretty high. As a result, they outsource what they can to manage costs. In maintenance that often means the use of repair stations or MROs for heavy checks. An MRO, on the other hand, is really good at being an MRO. They have met all the requirements for compliance to Part 145. In addition many have extensive qualifications and certifications for use of state of the art management and maintenance processes. But they don’t operate aircraft for hire. So the business needs are different and have to be harmonized in some way that results in successful projects to mutual benefit.

Air carrier audits are only one part of the MRO evaluation

It seems fairly simple on the surface. The repair station accomplishes the work per the operator’s maintenance program requirements. It’s audited to check its ability to do so. The checklist is fairly common and covers all of the elements necessary to verify that they are compliant. But, as a rule, auditors are checking for compliance to 145 and MROs as I have said are good at being MROs.

Production aspects and processes while visible to auditors and air carrier personnel are not always understood. MRO personnel are expected to meet the expectation they created when they sold their service. But the service did not explain the means by which the MRO expects to accomplish the project. Audits don’t account for the skill of the MRO when unexpected events occur such as an unanticipated inspection finding that creates more ground time than the air carrier planned. Further the production and planning process from the air carrier to the repair station differ. A repair station is geared to load and unload the aircraft to manage the labor to a budget. With labor cost normalized to daily staffing these considerations don’t largely concern air carriers. They are not deriving revenue from the check; their goal is to arrive at the gate on time with a quality aircraft. MROs have to deliver aircraft on schedule but have to make money at it. Processes are devised to monitor and control resources on a heavy check so that anticipated revenue from the project is realized.

Check plans established by the air carrier must take into account the labor that the MRO has available. If there are additional lines of work in the hangar from other customers these lines are not independent of each other. They are sharing resources. Most MROs do not have sufficient resources to commit personnel, tooling and administration exclusively to each aircraft line. There is always some level of sharing between projects. There is also competition. One project manager is struggling to make his output date and the loss of key persons or equipment for a new project can impact his delivery goal. An auditor can look into these situations when evaluating the MRO. He can, with practice, assess the operator’s project controls and support processes as a method of evaluating project management strengths and weaknesses.

Special requirements by the operator created by provisions in their vendor instructions may hobble heavy check performance. The rule states that the MRO must comply with applicable portions of the operator’s maintenance manual. Application of the operator’s internal standards to the repair station activities are not assessed on their effect on the project. Often, when this is pointed out by the MRO the rejoinder is that they must follow their manual requirements as they direct. This is true. They must. However, everyone’s concept of what constitutes the “applicable portion” is different. The devil is in the differences.

Industry standardization would help

Having watched all of this from both sides it would seem to me that the best low hanging fruit for improvements in this area is an effort to standardize those processes that are mutually shared in getting an aircraft back in the air. Manage the interface. For example, both operators and MROs use nonroutine forms. Industry level standardization of nonroutine records could be devised in a format that could be used across both computerized and “hand managed” platforms. A standardized nonroutine format with generally accepted methods of execution would relieve everyone of the need to address incompatibility of formats when trying to manage discrepancy and repair data.

Now this may seem trivial to many, but, beyond routine tasks cards provided by the operator, nonroutine task cards are the most used form of the project. It is the vehicle that records all of the maintenance accomplished for check findings. Between the MRO and operator its format and presentation is currently what the imagination can make it in flavors both hardcopy and electronic. It’s the key product that records the maintenance performed and provides the information to create the bill. Just from an economic point of view alone, it’s worth considering. Standardization here may have benefits largely by creating repeatability in aircraft quality and reliability simply by giving everyone an accurate idea of what is going on.

A good example of a successful standardization effort was the development of the 8130-3 Authorized Release form. Capable of being completed electronically, or by hand; stored electronically or in physical files; with a standardized method of completion for a variety of conditions. And everybody these days uses it. It’s almost currency.

Will SMS have an impact?

Safety management systems (SMS) will eventually get around to making us all reexamine our outsourcing policies and processes. In doing so, operators will have to understand more than Part 145 compliance aspects. In choosing an MRO each operator should make the effort to evaluate the interface between them and their new partner. The decision to use or pass on outsourced maintenance will have to be based on the compatibility of the MRO's production system with their own production and compliance goals as an aspect of SMS evaluation.

For example, if an MRO has invested heavily in Lean processes to produce internal efficiencies, the operator’s quality organization can impose un-optimized processes undermining the MRO’s Lean implementation. This can affect both parties’ quality and production expectations. The operator must be prepared to address these issues in comparison to their own internal requirements. Their assessment can allow adjustments to meet its program requirements but align it to take advantage of the MRO’s improvement efforts.

Another tool that can define and refine the relationship between operators and MRO is the airworthiness agreement. While business contracts define the invoice, the airworthiness agreement defines the compliance state of the aircraft in the context of a conversation between the MRO and air carrier maintenance organizations. Defining the processes and certification standards that take into account the repair stations needs creates more predictability in the project outcome and improves communication.

In assessing the MRO, the air carrier in the 21st century can no longer rely on repair station compliance audits as a means to judge the probable outcome of an aircraft heavy check project. Some assistance from the regulator in creating work record standardization would allow the industry to design an interface that would bring commonality to production management. In moving to the SMS environment carriers now need to assess their own processes effects on vendors when engaged in out sourcing. By defining the interface between themselves and the MRO they will be able to address and standardize processes and controls. In doing so, they create a relationship with their repair station partners that can promote a high level of quality and repeatability in aircraft deliveries.

About the Author

Vern Berry

Vern Berry began his aviation career as an A&P mechanic in 1979. His experience within the aviation industry includes key management roles in quality and safety for both MRO and air carrier operations. He and his wife currently reside in upper state New York where he writes and manages a consultant firm at www.blowntireaviation.com.