Concerns over how to prevent the spread of Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) are growing as the disease’s death toll climbs. And airport officials are among those expressing concern.

Their worries seem valid as there have been 688 confirmed infections and 282 deaths to date from this deadly disease.

And Dr. Kamran Khan, an infectious disease physician, warns these numbers will likely escalate as pilgrims pour into the Makkah Region in Saudi Arabia to perform Umrah. More pilgrims are expected to arrive with the approach of the fasting month of Ramadan, which started in June. But he predicts numbers will really rocket when pilgrims come for Haj, the largest annual religious gathering worldwide, which takes place in October.

“There are millions of pilgrims from around the world about to converge into Saudi Arabia, where there is an outbreak of MERS,” he says. “This disease is a cousin of SARS. It is not as contagious, but it’s more deadly. And there is no vaccine or treatment for it.”

While this infection doesn’t spread as easily as influenza, it’s still a concern at the nation’s ports. Airports in Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Dallas-Fort Worth and San Diego have responded by posting health warnings for travelers alerting them to the potentially deadly disease.

But it shouldn’t take an outbreak for airports to begin thinking about pandemic preparedness, says Khan.

“Nearly every year we see a brand-new infectious disease we’ve never seen before,” he explains.

According to Khan, the founder of Bio.Diaspora, a company that has developed a tool to help governments decide whether or not to screen airline passengers leaving or arriving from areas of infectious disease outbreaks, the primary drivers of this are things like:

- Population growth (there are 7 billion people on the planet today);

- Disruption of wildlife ecosystems (displacing animals from their homes);

- Climate change, urbanization (putting more people in close proximity to another); and

- The ease of travel (there are close to 3 billion people boarding flights every single year), says Khan, the founder of Bio.Diaspora, a company that has developed a tool to help governments decide whether or not to screen airline passengers leaving or arriving from areas of infectious disease outbreaks

“All of these things contribute to the emergence of new diseases and the accelerated spread of disease,” says Khan. “The global airline transportation network helps diseases find a new home.”

Dr. Nicki Pesik, a medical officer in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, agrees. “We are in a globally connected world and one infected person can carry a disease to any place in the world in 24 hours.”

For this reason airports need to be ever vigilant and ready with a plan of action should disease strike.

So how does an airport protect travelers from disease?

“You begin with a solid understanding of how disease is spread,” says Dr. Philip Tierno Jr., associate professor in the departments of Microbiology and Pathology at New York University Medical Center. “Eighty percent of all infections are transmitted by direct or indirect contact,” he says.

Direct exposure would be through things like sneezing, coughing, kissing, anything that would directly transmit one person’s germs onto another individual. Indirect contact would be transmitting germs by having hands that just wiped a runny nose touch a moving walkway rail so that when another person comes along and touches that surface they come in contact with those germs. Then if that person touches his or her mouth, eyes, nose or an open wound, it gives these microbes a path into the body.

This knowledge is followed by prevention, pandemic preparedness exercises, traveler communications, staff education, and keeping the facility as clean as a mass transit center possibly can be.

Prevention Is the Cure

There are three frontiers where something can be done about infectious disease outbreaks, says Khan. The first is to try and address the infectious disease before it spreads. This is the most preferable approach because the event can be contained within a defined geography. Authorities can intervene at airports or as people travel, but if travelers are not displaying symptoms their efforts will be wasted. Finally, officials can respond to the infectious disease in their own backyard, after it has spread beyond a country’s borders and the airport fence, but then they are reacting to the disease’s introduction to a community rather than taking a preventative approach.

To aid airports in preventing or delaying the spread of disease, Khan has developed a tool that aims to address social and health issues associated with the globalization of infectious diseases. Bio.Diaspora monitors infectious disease activity around the globe, connects it with information on global mobility, and contextualizes that information with other data sets that include things such as demography, animal and insect populations, real-time climate conditions from satellite data, social media, and global travel patterns.

“We can use that information to quickly gauge what parts of the world are at risk for having a significant impact from a specific disease,” says Khan. “While you can’t prevent everything, in many cases, using a tool like Bio.Diaspora, you can prevent or mitigate the impact of an infectious disease event happening in another part of the world.”

Bio.Diaspora aims to help governments across the globe determine whether to screen airline passengers leaving from or arriving at areas of infectious disease outbreaks. “This allows us to notify public health authorities and give them a heads up, so that they’re anticipating threats rather than reacting to them when they arrive,” says Khan.

Khan’s research has revealed that a focused and coordinated passenger screening process during times of outbreak can greatly benefit public health. Screening travelers as they leave or enter an area where infectious disease is present, he says, is far more efficient than screening passengers once they land at their destinations.

Plan Ahead

Prevention, however, can only go so far. Microbes have an incubation period from the time an individual is exposed to a given disease and becomes infected, and when they develop signs and symptoms of illness. In today’s globally connected world a contagious traveler may visit another country and return home before they show any signs of disease.

“Even with illnesses that have really, really short incubation periods, like 24 to 48 hours, it’s still slower than the time it takes to circumnavigate the globe,” Khan says. “Today you can be infected, carry a microbe around the globe with you and not even know it until you get back. That’s what makes this a really big challenge. The speed of travel is faster than the incubation period of microbes.”

For this reason, the CDC encourages airports, airport businesses and airport partners to conduct planning exercises for outbreaks, according to Pesik.

These disaster drills should include critical partners across the airport and in the community, such as industry officials; emergency management agencies, including EMS, police and fire; state and local health authorities; and federal agencies. “At emergency planning exercises, the CDC can provide guidance to help airports respond to sick travelers during outbreaks that can affect the community,” Pesik says.

These exercises can help airports develop a preparedness plan that identifies a clear contact point for policy preparedness and the individuals responsible for operational implementation of the plan. The resulting strategy must focus on communications, screening, logistics, equipment, entry/exit controls, and coordination with local public health, according to Airports Council International (ACI) guidelines developed during the H1N1 scare in 2009.

Community Communications

When disaster strikes, communicate, communicate, communicate, says Pesik.

The CDC has reported two confirmed MERS cases in the United States, one in Indiana and the other in Florida. The two cases are unrelated but can be traced back to Saudia Arabia, reports the CDC.

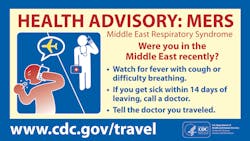

In response, 16 of the nation’s airports, deemed most at risk for transmitting this infectious disease, have posted signage that alerts travelers to the MERS threat. Because the risk of getting MERS is low, the signage does not advise travelers to change their plans but rather warns those heading to the Arabian Peninsula to take appropriate actions to prevent exposure.

“Wash your hands with soap and water. If soap and water are not available use alcohol-based sanitizers, and avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth,” the signs say.

“The best way of preventing the spread of disease can also be the simplest,” Pesik explains. “Help each person take everyday precautions. Remind them to wash their hands and avoid touching their eyes, nose and mouths.”

Appropriate signage should also recommend that individuals delay travel if they feel ill, and not travel until their symptoms subside. “Unfortunately, many individuals may not show symptoms when they move through the airport and by the time they fall sick they’re already in the United States,” she says.

During an outbreak, airports will want to distribute these public health messages to travelers, airport employees and staff. The messages can be placed on the airport’s website, intranet and social media pages as well as on signage inside the airport itself. “These systems allow airports to provide messages and updated information quickly as a situation evolves or changes,” says Pesik, who notes during an outbreak the CDC provides up-to-date health advisory messages to display at airport security, in Customs and Border Patrol screening locations, and international baggage claim areas.

During an outbreak the CDC also provides training to Customs and Border Protection agents to help them recognize ill travelers and report them to the CDC. The organization provides similar education and training to airline employees as well. A section called Travelers’ Health at www.cdc.gov is one that airports can point employees and travelers to. This section explains how passengers can protect themselves on trips as it pertains to vaccinations, food, animals and more.

To help keep travelers healthy, airports should make sure all restrooms are fully stocked with an ample supply of soap and place hand-sanitizing stations throughout the facility, says Pesik.

Infection control also involves keeping the facility as clean as possible. “A [mass transit] facility can go from clean to dirty in a matter of minutes,” says Becky Gawin, deputy director of Facilities and Services with the City of Phoenix Aviation Department. In this role, she oversees aviation’s service contracts, which includes a contract for custodial services at Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport. Here 200 custodians clean the airport’s 5 million square feet of terminal space, from top to bottom, every single day.

While constant cleaning is essential in the busy mass transit facility, during an outbreak these services become even more critical. Gawin says Phoenix Sky Harbor puts cleaners on the concourses 24 hours a day, and some of these cleaners are assigned to constantly wipe high-touch surfaces such as handrails, chair arms, door handles and so on. To keep infections from spreading, high-touch surfaces must be identified and cleaned with a disinfectant in this way--every time a cleaner moves through an area.

Prevention, planning, preparedness and public announcements are among the ways that airports can address outbreaks before, during and after they occur. “Doing these things is not just good business, it can be life saving,” says Pesik.