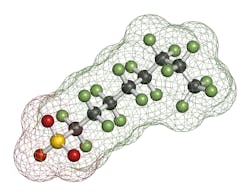

When aqueous film-forming foam, or AFFF, was introduced 50 years ago, its effectiveness at firefighting made it popular with emergency personnel at airports and military bases. Chemical compounds called perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) found in AFFF repelled both oil and water and smothered the flames quickly. AFFF created a foam blanket that put out fires and provided additional protection by suppressing fuel vapors and preventing reignition. Its use quickly spread, not just to put out fires but in equipment testing, training exercises and during fuel spills as a preventative measure.

Its effectiveness came at a cost, but airport and firefighting personnel were never told of the health consequences. Because firefighters weren’t aware of the health risks, AFFF was used frequently in training exercises at airports and other locations. The practice resulted in substantial AFFF soaking into the ground, local streams, watersheds, drinking water and ultimately humans.

For airports, particularly small ones, learning about PFOA and PFOS contamination in the soil or local groundwater supplies raises many questions. For example, did the contamination come from the airport personnel’s use of AFFF? Who is responsible for cleaning up the soil or the water? How much will it cost and who should pay?

Growing concern about PFAS

Today, research has shown PFOS to cause harm to humans and the Environmental Protection Agency has set a lifetime health advisory limit of 70 parts per trillion in drinking water. PFOS and PFOA are two of the thousands of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

Research has linked this toxic class of chemicals with cancers, kidney disease, low infant birth weights and hormone disruptions. Over the years, PFAS has earned the nickname the “forever chemicals” because they don’t break down in water or soil. As a result, firefighting foam left on the ground or spilled is still likely present, even decades later. Some may have been carried away by rain into aquifers or nearby streams.

Many state regulatory agencies now request or require water systems to test for an expanded list of these chemicals. Some states are enacting their own rules, regulations and enforceable standards without further federal action. Most states that require testing are requiring it at and near airports, and where PFAS are detected, site characterization is then also required. As drinking water is one of the most common ways humans ingest PFAS, contaminated water must either be abandoned or cleaned up along with contaminated soil.

Cleaning up PFAS in the water can be costly. Building and operating treatment facilities can cost millions of dollars. Cleaning up PFAS from drinking water is typically done at the wellhead, pumping it to the surface for treatment. Treatment includes granular activated carbon, ion exchange and reverse osmosis. Sometimes, treatment is not an option in which case the contaminated water may just be isolated while water systems find alternate drinking water supplies.

Airports in Focus

Rising concern about PFAS has led to new and evolving environmental requirements for airports. For example, the state of California requires drinking water wells located near airports to be tested for PFAS contamination, as airports are considered likely contributors. The U.S. Department of Defense is investigating past PFAS contamination and has identified more than 400 military sites with significant legacy PFAS concerns, many of them at airbases or airports.

Congress had set an October 2021 deadline for the Federal Aviation Administration and an October 2024 deadline for the Department of Defense to convert their AFFF to fluorine-free firefighting foams. North American manufacturers have replaced PFOS and PFOA with other PFAS substances in their AFFF formulations. Still, rising concern about detrimental health effects of the entire PFAS class of chemicals means that other alternatives are being mandated.

Airports Pursue Legal Strategies

As airports face an evolving regulatory environment, many of them are considering joining property owners, personal injury plaintiffs, water systems, states, territories and tribes in a multidistrict litigation (MDL) suit. The plaintiffs allege that the companies that made and sold AFFF containing PFAS knew these chemicals were harmful to human health and the environment but concealed the information.

MDLs are used to coordinate complex litigation filed in multiple federal district courts by similar parties. By consolidating the discovery and pretrial motions, both sides save time and money.

The benefit for plaintiffs is that attorneys can pool their resources and coordinate efforts to take on large, powerful corporations. If early cases are resolved in favor of the plaintiffs, it usually results in a domino effect of settlements for the remaining cases. Typically, the presiding judge will steer the parties toward an agreeable resolution with a national settlement. An MDL settlement is not binding on any party without their agreement to participate, but it can provide efficiencies. If a case is not settled during an MDL, it is sent back to the original court for trial.

When Legal Claims are the Best Option

While the costs for cleaning up PFAS can be high, taking legal action doesn’t have to cost money upfront. Some law firms, including SL Environmental Law Group, front the costs of filing the lawsuit and only get paid if and when the case is won. This type of arrangement is known as a contingency fee. A contingency arrangement is especially helpful to small airports with limited financial means, but airports of all sizes benefit from the structure, reducing the risk of participation.

Additional plaintiffs can still join this MDL-2873, which is likely one of the faster routes to a party if it has been polluted by AFFF. Proceedings are already underway for water providers, which effectively shaves off two years (the duration the MDL has already been pending) to settlement or trial verdict and making now a good time to join.

The Department of Defense has estimated that the cost of cleaning up PFAS contamination at its sites could cost more than $2 billion, but the reality is that no one knows what the full cost will be. The enormity of PFAS contamination is just beginning to be realized and could rival the clean-up of asbestos and lead. This has led to a consortium of legal firms that are well-equipped to handle complicated legal, scientific and political issues involved in these types of cases.

Suing the parties responsible for the pollution is a smart solution that helps pay for critical treatment costs. The chemical companies that caused the contamination should bear these costs. The law holds those companies liable for the problem, which is why many U.S. airports impacted by PFAS contamination are seeking legal counsel. When the safety and health of future generations are at stake, using every tool to tackle the challenge just makes sense.

Ashley Campbell is currently the lead contact for all PFAS contamination cases at SL Environmental Law. She represents over 40 water providers, airports and public entities in a multidistrict litigation(MDL) suit relating to PFAS contamination from aqueous film-forming foams. Ashley is the MDL co-chair for the water providers committee and is a member on the sovereign committee.

Seth Mansergh has worked at SL Environmental Law since 2009. His focus is representing public entities in groundwater contamination litigation including cases involving 1,2,3-TCP, MTBE, and PFAS.