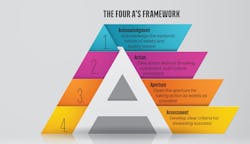

Systemic safety and quality problems can develop even in otherwise widely admired organizations. Safety-critical businesses should tackle these as quickly and as thoroughly as possible. This article proposes a framework — the Four A’s — for addressing systemic safety and quality issues.

Top Priority Mission

Individual errors can occur even in the best managed organizations and often are costly. Systemic problems can develop even in the most admired of organizations and can become existential threats. Aviation and other safety-critical businesses should be particularly alert to the development of safety and quality problems that are potentially systemic. These should not be allowed to fester and to become entrenched. Aviation businesses should make correction of systemic safety and quality issues a top priority mission. This article proposes the Four A’s framework as a helpful managerial tool for executing this important mission.

The Four A’s Framework

The building blocks of the Four A’s framework are acknowledgement, action, aperture and assessment. These are discussed individually below:

1. Acknowledgment — Acknowledge the systemic nature of safety and quality issues.

Deliberate correction of a problem is contingent upon recognizing and acknowledging it in the first place. Unfortunately, in many organizations, the first gut reaction to the emergence of problems often is denial, deflection or qualification. This can be the case even for relatively small and inconsequential individual errors or violations.

Recognition and acknowledgement of systemic problems with potentially much graver consequences tends to be an even taller order. Some organizations refuse to recognize and to acknowledge the systemic nature of a serious problem, even in the face of overwhelming evidence. Rather than accepting an issue as systemic, leadership gravitates towards emphasizing its ostensibly individual nature. This tendency can be particularly pronounced in widely admired organizations that are recognized leaders in their domains and that have a strong sense of pride in their history.

Leaders of aviation businesses should not fall into the trap of discounting systemic safety and quality issues as individual errors or violations, let alone of dismissing them as “one off” Black Swan events. Instead, safety-critical businesses would be well-advised to acknowledge the systemic nature of safety and quality issues based on data-driven clear and compelling evidence.

2. Action — Take action without throwing overboard Just Culture principles.

Once the systemic nature of particular safety and quality issues has been acknowledged, appropriate preventive and corrective measures need to be devised and put into place.

One of the pillars of credible and effective safety and quality management are data-driven and no-holds-barred root cause analyses. These should not fall victim to non-data-driven guesses or politically predetermined outcomes. Best solutions for identified problems should be developed based on the outcome of the root cause analysis. In general, systemic issues usually require systemic solutions such as adjustment of an organization’s culture, HR management principles, operations architecture, standard operating procedures or resource base. More often than not, implementation of appropriate preventive and corrective measures that address systemic issues is a highly time-, effort- and cost-intensive undertaking. Organizations tackling systemic issues should beware of the temptations of pursuing “fast, frictionless and free fixes.”

Accountability of leadership is a key principle of good governance of any business. For those aviation businesses that are subject to regulatory certification and oversight, it usually is a regulatory requirement. In the context of addressing systemic safety and quality issues, leadership accountability becomes particularly salient. However, it is worthwhile emphasizing that organizational Just Culture principles should apply to any employee, no matter how junior or senior and no matter whether member of the executive ranks or not.

3. Aperture — Open the aperture for taking action as widely as possible.

When taking action to correct systemic safety and quality issues, organizations should cast their net as widely as possible.

Often, discovery of systemic problems is triggered by specific incidents or accidents in a particular sub-unit of a larger organization. For example, repeated post-maintenance findings of foreign objects left behind in aircraft fuel tanks can be a reflection of organizational culture or standard operating procedure deficiencies or non-compliances in a particular repair station. Consequently, when implementing preventive and corrective measures, attention tends to be focused on the sub-unit at which a systemic problem has emerged in the first place.

However, due to the inherent nature of systemic problems, it is unlikely that safety or quality issues are confined to a single domain within a larger organization. This is particularly applicable to multi-divisional, multi-site or multi-product businesses. For example, in the case of a multi-site MRO with one group-wide organizational culture and process architecture, how likely is it that occurrences of foreign objects left behind in fuel tanks are limited to a single site? Or, in the case of a multi-product OEM with shared engineering resources and incentive system, how likely is it that systemic design approach deficiencies are limited to a single product?

When addressing systemic safety and quality issues, aviation businesses would be well-advised to open the aperture of their efforts as widely as possible and not fall victim to a potentially gravely consequential “single division, single site, single product only” fallacy.

4. Assessment — Develop clear criteria for assessing success.

Recognition of successful resolution of systemic problems is as important as recognition of such systemic problems in the first place.

Organizations that have acknowledged and have initiated action to correct systemic problems need to have a clear definition of success. There should be clear and auditable criteria for assessing if a given problem has been fixed for good. In the case of aviation businesses that are subject to regulatory certification and oversight, at a minimum, such criteria are driven by compliance with regulatory standards and requirements. Of course, any aviation business can decide to set the bar against which it measures its safety and quality performance to a level higher than mandated by regulatory requirements.

To invoke an aviation analogy, recognition that one has cleared hazardous weather and can safely return to one’s planned flight path is as important as detecting and avoiding hazardous weather in the first place. Such determination is best based on clearly defined, data-driven criteria rather than on improvised, ad-hoc hunches.

Avoidance of Adverse Consequences

Correcting systemic safety and quality issues can be one of the most challenging leadership endeavors. Failure to address systemic safety and quality problems with the right sense of urgency and level of resource dedication can result in grave moral, reputational and financial consequences. The Four A’s for addressing systemic safety and quality issues outlined above are intended to be a potentially helpful tool for leaders of aviation and other safety-critical businesses to avoid these consequences.

Dr. Marc Szepan is a Lecturer at the University of Oxford Saïd Business School. Previously, he was a senior executive at Lufthansa. His primary professional experience has been in leading technical and digital aviation businesses based in Europe, Asia, and the U.S. He received his doctorate from the University of Oxford.