As director of product support for Hartzell Engine Technologies (HET), a producer of turbochargers for certified aircraft piston engines, I get a lot of questions from aircraft owners and mechanics regarding these sophisticated units.

And, in most cases, it becomes clear that the problem or at least the origination of the problem was the pilot’s or mechanic’s lack of understanding of how a turbocharger system functions.

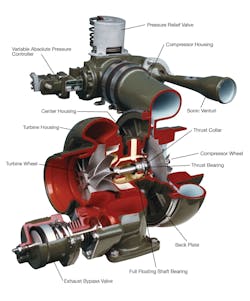

So, let’s start with a short turbocharger primer: Today’s turbocharger is just one part of a diverse system. That system consists of the turbocharger, controller, pressure relief valve, and wastegate, and that along with the engine’s exhaust/intake assemblies, complete the system. And while the turbo itself seems like a simple device, it is in fact a very precise component that can operate at speeds over 100,000 rpm and at temperatures exceeding 1,650 F.

Most problems begin as a failure to communicate

In our experience, the majority of the returns we receive from the field are found not to be issues with the turbocharger itself, but in most cases they are problems with the system’s installation, inadequate pre-lubrication, or other operational issues.

Typically a mechanic must inspect and diagnose operational issues that may include an inability for the aircraft to reach altitude; pressurization issues; the system’s inability to reach the maximum-rated manifold pressure; a surging or dropping off of manifold pressure when climbing or descending; and/or oil leaks from the compressor or turbine side of the turbocharger.

To help avoid many of these issues, pilots flying turbocharged aircraft need to keep a close eye on their aircraft’s engine/exhaust system. Why? Well, in many of the cases the system will give the pilot or mechanic telltale signs of pending issues.

For example, when there are the beginnings of a problem with a turbocharged engine you will usually get nuisance-related maintenance items: a bit of extra oil consumption, a slight leak, a bit of blue smoke from the exhaust, or possibly oil collecting at the exhaust outlet. Spotting any of these are clues that now is the time to look deeper into the system’s health.

That’s why we strongly suggest that owner/operators be very proactive in their maintenance especially when it comes to oil changes. Since the turbocharger shares the oil system with the engine, mechanics should recommend that owners routinely change the oil between 25 to 35 hours. The condition of the oil can provide an indication regarding the health of the turbocharger system.

In addition, during the oil change, the mechanic should take the opportunity to give the entire engine and turbocharger system a thorough inspection. Make sure the air filter is clean and check the security of the intake and alternate air systems to prevent FOD (foreign object debris) from entering the compressor or from robbing the compressor of air. Also, take time to visually inspect all clamps, hoses, ducts, and related components of the intake/exhaust system.

Before all else fails, remember the following…

Heat and/or lack of oil are the common denominators in most turbocharger failure situations. With that in mind, mechanics need to be just as diligent with the engine power management during ground operations as pilots are in flight – and even more so.

Improper engine shutdown after a ground run is the most common mistake mechanics routinely make. The required static run-ups after an inspection or repair spool the turbo up to its full potential. Mechanics typically shut the engine down to make adjustments without giving the turbo time to spool down.

Shutting down the engine starves the critical turbo components of oil and that can lead to significant damage. Yes, it’s tedious and time consuming, but mechanics must follow the same engine shutdown procedures after a 10-minute ground run as a pilot returning from a four-hour flight. You must follow the aircraft’s POH and allow the turbo time to spool/cool down prior to shutdown.

Remember that the system’s lubricating oil is coming directly from the engine’s oil system. Shutting down the engine stops the flow to the turbocharger at that moment. If the turbocharger is still turning at a high rate of speed, any stagnant oil remaining around the extremely hot turbine shaft will overheat and ‘coke’ or burn.

Along with coking, bearing damage can occur and cause the bearings to “orbit” as opposed to spinning. This will ultimately allow contact between the wheel and the housing, which will lead to premature wear and failure.

Time for a change?

OK, the turbocharger is showing signs of distress, what’s next?

First, perform a visual inspection of the turbine and compressor wheels. Focus on any nicks, dents, corrosion, or other signs of damage. None of these conditions are repairable.

Next, verify that there is no contact between the wheels and respective housings. Stick your finger into the oil outlet port and feel how much sludge exists. Excess sludge will hinder oil flow and scavenging, leading to oil leakage.

Now, perform a radial and axial bearing clearance check. Remember that clearances that are greater or less than those specified are suspect. Excessive clearance can indicate excessive bearing wear, while tight clearances may indicate excessive coking buildup.

Turbocharger systems rely on very sophisticated components with tight tolerances and little room for error. Because of that, field repairs are not something the typical shop should attempt. That leaves the question of what type of replacement to buy: overhauled, rebuilt, or new?

That’s a question I get asked a lot. It’s not an easy answer. While we do offer factory rebuilt turbochargers, by the time you factor in the core exchange charges and shipping costs, the option of buying a factory new turbocharger becomes very attractive. The simple reason is that by FAA regulatory definition a rebuilt turbocharger has to meet the same standards as a new unit.

So if rebuilt and brand new turbochargers are basically the same, what about a field overhauled unit you ask?

Well, overhauled units are not required to meet ‘new’ standards so they can be less expensive. But the thoroughness of the overhaul depends on the shop doing the work. The typical field overhaul shop will probably reuse more of the original parts than we will here.

There’s nothing wrong with that as long as they follow the latest manuals, service bulletins, and service instructions for inspecting and overhauling HET turbochargers, valves, controls, and wastegates, and replace all the required parts as indicated.

The operative statement here is: “follow the latest instructions and manuals…” So you, Mr./Ms. Mechanic, need to do your homework. You need to talk to the overhauler and ask if they do have and comply with all the manufacturer’s latest instructions and provide a detailed list of all the components they change during an overhaul. If they won’t supply one, move on to another shop. And if they do give you a list, pay close attention to whether or not they change critical components like the bearing housing (also called the center housing) and the turbine wheel assembly.

Components like the turbine wheel are subject to fatigue and thermal stress. And the effect of fatigue damage is cumulative, and not always obvious, which makes it very hard to detect during an inspection.

For that reason, HET’s overhaul manual requires replacing critical components with new parts, which is the prudent course of action. It has proven to be the best way to help ensure that critical parts will make it through to the next overhaul cycle.

We also initiated a recommended service facility (RSF) program. Participating turbocharger repair and overhaul facilities have agreed to follow the HET overhaul manuals and only use genuine HET parts. Currently, Quality Aircraft Accessories of Tulsa, OK, (www.qaa.com) is an HET RSF.

Another point to consider when making the new vs. rebuilt vs. overhauled decision is that new, and often times rebuilt units will offer the benefits of having more new-generation components that are manufactured using the latest equipment, materials, and techniques.

Tim Gauntt is director, product support, for Hartzell Engine Technologies.