SARASOTA, FL — Airline and airport analyst Mike Boyd predicts mixed blessings for the aviation industry. Speaking at The Boyd Group’s annual Aviation Industry Forecasting Conference in October, he observed that “everything’s going to be very different in the way things are done, where they’re done, how they’re done — and most of the news is good.” Boyd says U.S. airports should be looking at how they connect internationally, which may present new opportunities. He remains a critic of air traffic control modernization, and calls for a rethinking of the Essential Air Service program. High on his radar is the changing complexion of the low-cost carriers, led by Southwest and Frontier.

To really be a player anymore, Boyd says, airports have to be connected to the global network in some way, shape, or form.

“America is no longer the center of the universe,” Boyd says. “And what’s happening is, global transport, global trends are what’s going to be driving things, not just in New York City, but they’ll being driving things in Gainesville, they’ll be driving things in Fresno.

“We are part of a global industry. And for aviation, that’s going to be critical going forward.”

Garnering international traffic, Boyd says, is one the best ways to stay relevant. “Communities that are connected, air service development-wise, to the rest of the globe are going to grow,” Boyd says. “Those that are not, are not going to grow. It’s just as simple as that. That’s why economic growth is going to be very critical at international connections to get air traffic growth.”

China, as usual, will be a big part of re-thinking traffic flows in the United States. Says Boyd, “There’s a tremendous amount of traffic between growing trade routes between Latin America and China.

“There’s probably enough people to fly non-stop between Sao Paulo and Beijing, if an airplane can make it, but you’re talking about a lot of secondary cities. How do you get those people back and forth? You can’t fly non-stop from Chihuaha to Beijing, it ain’t going to happen.”

The answer for U.S. airports, Boyd says, is to become ‘global portals’ connecting not just domestic regions but global regions as well. “Look at a globe and draw a line from Rio de Janeiro to Beijing. You’re going right over the United States,” Boyd says.

Boyd envisions Detroit, Houston, and Dallas-Fort Worth as all being good global portals candidates, which in turn will help drive domestic travel to smaller U.S. cities. The Boyd Group also has been studying other international traffic flows within the United States.

“India is a prime example,” Boyd says. “Over 2 million Indians are living in the United States. Of them, 60 percent, according to the Indian government, have maintained their Indian citizenship. In other words, you’ve got one-point-something million people living in this country, but they’re Indian citizens.

“What that means is they travel. Another point they have is they’re about 25 percent above the average in the U.S. in terms of income. It’s a very lucrative market, and it travels back forth.”

Air traffic and the Hill

“Air traffic management in aviation is going to be an ongoing problem,” Boyd says. “We really don’t have leadership. Until we do, there’s going to be more and more constriction on our air transportation system in the United States.”

And the airlines are at least partially to blame. “ATA comes out saying they want to work with the FAA,” Boyd says. “Fine, you want to work with your captor.”

“Forget NextGen. That’s yesterday-gen. The FAA’s own annual report said ‘all our programs are on track. Our wide-area augmentation system will do this, this, and this.’

“They left out that the wide area augmentation system is 13 years late. The reason it’s on track; they just gave it a new schedule. Which is like arriving on a flight three hours late and the pilot telling you ‘we’re on time, we changed the schedule in-flight.”

“So it’s one of those things to be very careful going forward when you hear the FAA or the ATA talking about how this NextGen thing is going to help everything. Or reauthorization will buy that new air traffic system we need. No, it won’t. FAA’s been screwing it up for the past 20 years.

What’s going to change there?”

The reauthorization debate at this point, Boyd says, is moot. “Arguing over who pays for reauthorization right now is like arguing over the bar tab on the Hindenburg. It’s all going down. It’s not going to get fixed.”

“The airline industry is going to have to take it into their own hands,” Boyd says.

“But it’s a system where, to keep us safe, they’ve got to keep airplanes separated more and more and more. They’re talking about how delays are up this year. Departures are up about one percent for the first half of this year. But delays are up 40 percent. Gee, I wonder why that is? It’s not because of more airlines in the sky or more passengers. It has everything to do with a system that doesn’t really work.”

Peak pricing, Boyd says, will not work either — just raise costs. “Some hubs like Atlanta, there is no peak,” Boyd says. “It starts at six and goes until nine — there’s your peak.”

Will Ris, senior vice president of government affairs for AMR Corporation and American Airlines, relates that much of the problem on the Hill has to do with how Congress approaches the aviation industry. “I believe that policy-makers treat our industry fundamentally differently than others,” Ris says. “They react first as customers and only secondly as policy makers.”

“These people, these men and women on Capitol Hill, are some of the most voracious consumers of our product. They fly often, and often on extremely tight schedules. So a good deal of the policy and the debate that we have in Washington is formed on the basis of anecdotal experience and gut feelings from a consumer viewpoint.”

The nature of the aviation industry impedes the process as well, Ris says.

“We are so risk-averse in our industry that we continue to postpone and avoid the really big changes that are absolutely necessary for our long-term survival. Indeed, avoiding risk is a core component of our industry culture, and often for the right reasons. We have let our aversion to risk spread to the economic and production regions.”

“The principle debate in Washington is much more about how to reduce demand than it is to increase capacity. We are being called together collectively to talk about how we can reduce our scheduling in the New York airports as opposed to being called together collectively today — and years ago — to talk about how we can expand capacity to allow the capacity to meet the vigorous demand.

“Right now in Washington we are in absolute political gridlock with respect to reauthorization. My prediction is that we will muddle through the reauthorization debate, compromises will be made, studies will be promised to take some issues off the table, everyone’s taxes will go up, and we will again have missed an opportunity to do something of real significance.”

Air Service Outlook

For airports, Boyd says, quality, not quantity, is going to be the most important thing for air service.

“What are the load factors, but more importantly, what are the yields in those markets?” Boyd says. “What’s the fee ratio? That’s critical going forward. You might have an 80 percent load factor, but if 70 percent of that’s going on to Orlando with really low fares — goodbye.”

Traffic generation, both inbound and outbound, is also critical to an airport’s success, Boyd says. Striking the right balance is key.

“If you have a lot of traffic — more than, say, 55 percent of your total mix is generated from outside your marketplace — the good news is you’re not as dependent on changes at your marketplace,” Boyd says. “In other words, that factory closing or opening jacks traffic up or down, more than it would at a community where most of the traffic’s coming in.”

Boyd cautions that the Essential Air Service (EAS) is also a problem, and would need to be at least quadrupled in some cases to be effective. “We’ve got to do something with EAS,” Boyd says. “Because our forecast shows any EAS city is going to end up being stable at best, and in many cases you’re going to just end up having service nobody wants to get on.”

Meanwhile, Boyd says that airport design will need to change to be more efficient and meet passenger needs. “Going forward, you don’t need airports the size you do now,“ he says. “You need 100 linear feet of ticket counter space, when there’s no more tickets? I mean, you can check in at a kiosk.

“That is going to change how airports operate, how airports are designed, how passengers are flowed, and it’s going to be huge.”

Airlines and Fleets

Boyd divides airlines into three categories — low cost carriers (LCCs), legacy carriers, and niche carriers.

“The two airlines to watch very closely are Southwest and Frontier,” Boyd says. “Southwest because they know they have to morph and change things, and when they do they’re going to be the nastiest competitor on this planet. Because what you see today isn’t going to be what you see three years from now.”

Frontier, he says, is innovating fleet diversity and getting rid of regional jets, instead opting to fly Embraer 170s. “So they’re moving the product line and they’re moving the diversity of the root system up, which means that’s kind of the harbinger of things to come for LCCs,” Boyd predicts. “The days of being able to just get into a 737 and make money are going out. You need diversity. So those are the two carriers people say watch what happens the next three to five years.”

Boyd relates that competition between LCCs is heating up and points to the current situation at Denver International: “What’s happened when Southwest and Frontier get into a cat fight, fares go in weird directions, capacity goes in weird directions, and then that will affect Cheyenne, that will affect Colorado Springs. And those are short-term things but that’s going to happen around the country.”

While lower fares are one result consumers will appreciate, these fights can also be the death knell for affected smaller airports, Boyd says. He uses the example of Philadelphia, where Southwest began fighting for share. As a result, Bloomington lost air service.

“The damage done by the leakage can be permanent at small communities,” Boyd says.

As far as niche carriers are concerned, Boyd expresses admiration for Allegiant Air, saying he cannot find a hole in the carrier’s strategy.

“It’s a cruise ship with wings. They go into Killeen, TX; they basically attack Wal-Mart because that’s where the discretionary dollars are coming from, and they fill up airplanes to Las Vegas and to Florida. There isn’t another airline in the world that wants to fight for that traffic. So it’s a home run.”

Still, legacy carriers have the best outlook, according to Boyd, because of their ability to generate revenue. “Having more revenue streams is more important than just having low cost. Revenue streams come from places like Shreveport, they come from places like Columbus, MS. They come from places where you have net growth,” he says.

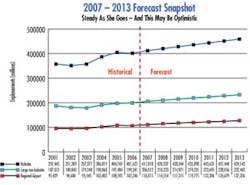

Boyd forecasts air traffic growth to drop below 2 percent annually in the next two years, and he doesn’t foresee the domestic carriers adding any real capacity. A stable economy — at best — is one reason; another is due to the buying patterns of airlines. “Virtually every airplane we see on order over a five-year period is not for growth,” Boyd says. “It’s just to replace what’s going to be retired.”

Yet, he says the size of the airplanes being retired does not necessarily predict the size of the airplanes being ordered.

“We’re in this situation where it’s very hard to forecast airplane demand based on seats,” Boyd says. “[Airlines] just want to move airplanes back and forth, which means airplane demand is more and more going to be focused on larger and larger aircraft. Because larger and larger aircraft is really where the real efficiencies are coming.”

“They’re going to be buying bigger airplanes, and maybe having lower load factors. There’s nothing wrong with carrying extra seats around as long as you’re not carrying any extra costs around.”

Boyd says he doesn’t see airline mergers happening, but alliances as being the future. Despite the money to be made, mergers are for the most part unnecessary.

AirTran’s attempted takeover of Midwest, however, is one exception to the rule. Boyd says his company did an analysis of the takeover, and saw nothing but good things coming from it, including more jobs and lower fares for passengers out of Milwaukee.

“Today, anybody who’s in Milwaukee who’s going to complain about fares, they’ve got no reason to complain. They didn’t want the merger, so now if they have high fares that’s their problem.”

Labor is also going to be a big issue for airlines during the next 18 months, he says. “They helped save the airline industry,” Boyd.

The fact is labor wants it back again, and regardless of how expensive oil is, regardless of anything else, you know labor’s not going to walk away from the bargaining table unless they get something back again.

“[Airlines] give away management bonuses — I don’t care if they’re due or not, you just don’t do that when your employees took 20 percent pay cuts. Labor has made it happen, labor wants it back again.”