On March 9, 2005, US EPA issued its long-awaited response to the aviation industry's repeated inquiries and requests for clarification of EPA's regulation of aviation refueler trucks under the Spill Prevention Control and Countermeasures (SPCC) rule found in 40 CFR Part 112. The response made clear that the Agency is now requiring secondary containment, which will have a major financial impact on the aviation industry, as airlines, FBOs and other fuel suppliers work with airport general managers to install secondary containment in refueler truck parking areas or demonstrate to EPA's satisfaction that such secondary containment is impracticable.

When we examine the purpose and intent of the SPCC regulations in the context of the unique airport environment, it appears that EPA has stretched its authority to regulate mobile refuelers by re-defining them. A history of the rule's application to mobile refuelers and the inherent impracticability of requiring secondary containment in the airport operations area, make it clear that EPA's decision is ill-advised. However, EPA has emphasized that there is a great deal of flexibility in engineering solutions for secondary containment to prevent oil discharges.

History and Purpose of the SPCC Rules

The SPCC program is administered by EPA's Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response. It requires facilities that store more than minimal amounts of oil (typically more than 1,320 gallons of oil in above ground storage containers) to prepare a SPCC plan which outlines how the facility will prevent oil spills from certain oil tanks and oil filled equipment. The stated purpose of the SPCC regulations are to prevent the discharge of oil from oil storage facilities into navigable waters and to ensure effective responses to such discharges. Even though a 1971 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between DOT and EPA exempted "transportation-related facilities" from regulation under the SPCC rule, the SPCC regulations appear applicable to transportation service providers like airports, airlines, FBOs and fuel providers. This is because under the terms of the MOU, the definition of transportation-related facilities refers only to highway vehicles and railroad cars that are used for the transportation of oil in interstate or intrastate commerce.

A Rose by Any Other Name

Specific provisions of the SPCC regulations require facilities to "position or locate mobile or portable oil storage containers to prevent a discharge…" In addition, mobile or portable oil storage containers are required to have "secondary containment, such as a dike or catchment basin, sufficient to contain the capacity of the largest single compartment or container with sufficient free board to contain precipitation." (These requirements are found in 40 CFR 112.8(11).)

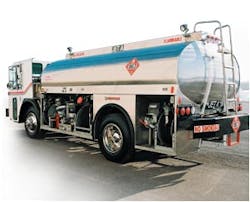

Engineers, environmental personnel and aviation consultants implementing SPCC regulations never dreamed that fuel delivery vehicles used to fuel aircraft would be considered "mobile or portable oil storage containers" subject to the secondary containment requirements. After all, the only purpose of airport refueler trucks is to deliver oil, not store it.

In 2001-2002, however, much to the surprise of the industry, EPA Regional Offices began issuing Notices of Violation to FBOs, fuelers and airlines for failing to install secondary containment around their parked mobile refuelers, even when refuelers were "parked" on the ramp or in the airport operations area. In defense, the recipients of the Notices of Violation argued that mobile refuelers were not mobile storage tanks subject to such secondary containment requirements. They also argued that EPA had developed a new interpretation of the meaning of "mobile and portable" storage tanks without the industry's knowledge, or the required notice and comment rulemaking. Even more important was the fact that containment for trucks was impracticable in the airport environment, where berms or containment basins would severely impede fueling efforts and aircraft movement. In addition, aside from one or two rare instances of intentional employee malice, no one within the industry could recall a situation where a parked mobile refueler truck sprung a leak. In fact, most spills occur during truck to aircraft fuel transfers, when operators are present and can respond appropriately to the spill.

Industry Efforts to Clarify the SPCC

After the Notices of Violations were issued, the aviation trade associations became involved, and began to meet with EPA Headquarters in Washington to voice industry concerns. NATA, ATA, AAAE and ACI provided information to EPA to demonstrate that the Agency's emerging interpretation that refueler vehicles were mobile containers was news to the industry and, in the case of the airport operations arena, completely impracticable.

Soon after these initial meetings, the EPA promulgated its final rule revising the SPCC regulations on July 17, 2002, but the final rule did not address the portable or mobile storage container debate. However, the preamble to the rule did address the meaning of impracticability.

After the final rule was issued, the EPA Regional offices appeared to recognize installation of secondary containment for refuelers when they were fueling aircraft was impracticable. They also seemed to recognize such containment was impracticable on the ramp when refuelers were in stand-by status. However, EPA continued to maintain that secondary containment was required for "parked" refuelers.

The aviation trade associations continued to submit comments to the Agency regarding the need for guidance regarding the issue, but received no definition of a "parked" refueler. In response, aviation consultants and attorneys began to advise airlines and FBO management to park their refuelers on the ramp when the refuelers were in service, or in loading rack or tank farm areas (where secondary containment was already installed) for longer periods of inactivity or overnight. At airports where drainage systems flowed to oil/water separators, the refuelers could be parked wherever any releases of fuel would flow to the appropriate drainage system.

On the legislative side, Senator Inhofe, the chairman of the Environment and Public Works Committee, became involved in the issue. He sent a letter to then EPA Administrator Christine Todd Whitman, requesting that the Agency issue appropriate policy guidance confirming the status of aviation fuel trucks as transportation vehicles and not storage facilities. Senator Inhofe pointed out, among other things, that the physical requirements needed to comply with the secondary containment rule "ran counter to the safe and secure operation of airports." EPA did not respond to his letter.

On March 31, 2004, EPA held a SPCC Stakeholders Meeting outside of Washington DC, to explain a SPCC litigation settlement, elaborate upon SPCC issues and address questions from the regulated community. At the meeting, EPA stated its emerging view that mobile refuelers are bulk storage tanks which require secondary containment. Mark Howard, of EPA's' Office of Emergency Response, indicated that the Agency would take further action on the issue, whether it be the issuance of informal guidance, formal rulemaking or enforcement priority.

In fact, on June 28, 2004, EPA published a notice in the Federal Register that it was considering a proposal to further amend the final SPCC regulations. The notice stated that the Agency was considering a proposal to amend the regulations in several different areas, including the applicability of the rule to mobile/portable containers. In spite of this notice, by the fall of 2004, several of EPA's regional offices continued with enforcement actions trying to resolve outstanding Notices of Violation involving the failure to provide secondary containment for parked mobile refuelers. Given the conflicting positions of the Agency, the aviation industry was uncertain as to what direction to take and whether to begin installation of costly containment in parking areas or wait until the issue could be resolved.

EPA Responds

Finally, on March 9, 2005, Craig Matthiessen, an EPA associate director in the Office of Emergency Management, sent a letter to the Director of Environmental Affairs for AAAE, providing EPA's final views on secondary containment for mobile refuelers. The letter states that mobile refuelers are "mobile or portable storage containers" subject to the SPCC rule requirements as originally promulgated in 1974 and that EPA has no plans to amend the SPCC requirements with respect to mobile refuelers. However, it will issue comprehensive regional guidance in August 2005 that will address the flexibility in engineering design solutions to provide secondary containment for parked refuelers. Matthiessen's letter also provided the following key information regarding impracticability in the aviation fueling context:

- When mobile refuelers are fueling, staged in operating locations or traveling to/from aircraft, sized secondary containment may be impracticable;

- Where it is impracticable, some facilities have used NFPA design guidelines and/or good engineering design solutions;

- Good and reasonable engineering design solutions are based on site-specific conditions and will not be unilaterally specified by the EPA; and

- While the applicability of design solutions must be evaluated by the facility owner and operator and certifying PE, owners and operators have some flexibility with regard to the secondary containment requirement.

As a result of EPA's response letter, persons in the industry with responsibility for health, safety and environmental compliance issues have a lot of work ahead of them. It will be particularly difficult to implement EPA's position that "parked refuelers" must have sized secondary containment such as dikes or catch basins to contain spills from largest compartment of truck. Because EPA recognizes that it is impracticable to install secondary containment around refuelers that are engaged in fueling operations, facilities with 24 hour operations may be luckier — arguably the refuelers are always engaged in fueling activity because they are always on stand-by status. However, bear in mind, that if a facility determines that it is impracticable to install secondary containment during fueling operations, the facility must meet the following requirements: 1) the facility's SPCC plan must demonstrate the impracticability, 2) the facility must have an oil spill contingency plan in accordance with 40 CFR Part 109 and 3) the facility must have a "written commitment of manpower, equipment and materials required to expeditiously control and remove any quantity of oil discharge that may be harmful, i.e. a contract in place with an emergency responder. (See 40 CFR 112.7(d)).

When considering impracticability arguments under the SPCC rules, EPA focuses on space limitations and safety concerns that prevent secondary containment from being installed in specific areas. For example, EPA's response to questions about impracticability from the EPA Small Business Ombudsman said this about impracticability:

A determination of impracticability from an engineering standpoint involves examination of whether space or other geographic limitations of the facility would accommodate secondary containment, or if local zoning ordinances or fire prevention standards or safety considerations that would not allow secondary containment would defeat the overall goal of the regulation to prevent discharges as described in § 112.1.

Secondary Containment Planning in the Future

EPA has extended the compliance dates with the final SPCC regulations discussed above until February 17, 2006, to amend an existing SPCC Plan and until August 18, 2006, to implement the Plan. However, because the Agency's position is that the secondary containment requirements have been in place for mobile refuelers since 1974, there is no extension for compliance with the secondary containment requirements for refuelers. Craig Matthiessen indicated that the EPA Regions would not delay enforcement actions until the comprehensive regional guidance mentioned in his letter is issued in August 2005. Therefore, aviation facilities should begin to examine their mobile refueler parking situation. They need to ensure that parked refuelers, which are "not engaged in, or traveling to or returning from fueling activities," are parked in areas of secondary containment. Engineers and consulting firms need to develop creative and low cost methods for the design and installation of secondary containment in these areas. These could consist of paneling systems, curbing or temporary booms that can withstand heavy truck traffic and operator error (such as failing to close curbing gating). Solutions may include:

- Relying on measures such as staging spill response materials in areas where trucks are parked, storm drain covers, increased inspections and additional training to alleviate or contain a release,

- Development of a 40 CFR 109 "strong oil spill response plan," demonstration of a formal relationship with an Oil Spill Response Organization (OSRO) and additional spill response training to provide strong oil spill response capabilities; and

- A written pledge in the SPCC Plan to work in good faith with the airport authority and other interested parties toward a permanent solution.

Since no one in the industry has mounted a legal challenge to EPA's interpretation of mobile or portable storage tanks (on the grounds, for example, that the Agency has created a new rule without complying with formal rulemaking requirements), the industry must be prepared today to comply with the relevant applicable SPCC requirements with new solutions and flexibility.