Aviation contributes about 2% of global greenhouse gas emissions—a percentage that the Air Transport Action Group predicts will increase without a switch to sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). But sustainable fuels aren’t the only way to attack aviation’s fuel use and emissions.

A new system from Aircraft Towing Systems World Wide (ATS) tackles the problem from the ground up.

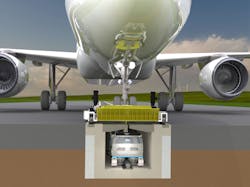

The company, based in Edmond, Okla., has introduced a concept that uses electric tow cars that run along below-grade tracks on airport ramps and taxiways to pull planes from the taxiway to the terminal. ATS is building a prototype at Ardmore Industrial Airpark in Oklahoma and will begin testing the finished concept in June.

According to Vince Howie, senior vice president and CEO at ATS, the best place to tackle aircraft emissions is on the ground.

“Aircraft are noisy, you can smell the gas and they burn a ton of fuel,” he says. “The most noticeable emissions are those planes emit on the ground.”

Howie stresses the ATS innovation ushers in tremendous potential for environmental savings and meeting future emissions limits. The development also comes at the right time. The European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has already released goals for engineless taxiing by 2050. Eventually, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) will too.

Consider that Boeing 737s and Airbus A320 aircraft comprise about 80% of the commercial aviation fleet and burn about 9 gallons of fuel per minute during taxi, with an average taxi time of 16 to 27 minutes. Add in that when operating at normal capacity, the average commercial large airport could see such movement 800,000 to 900,000 times a year.

“If an aircraft uses 9 gallons of fuel a minute for 16 minutes, 800,000 times a year, and fuel costs $2-$3 a gallon, you are talking some real money,” Howie says. “The savings our system will offer is huge.”

He adds the system not only saves fuel but slashes emissions. Pilots can turn off engines as electric tow cars pull the aircraft.

“You cut emissions by up to 80% when you turn off the main engines,” he says. “The APU is the only thing that stays running to power air conditioning and provide power to aircrew and passengers.”

Turning off engines also reduces noise.

“The noise reduction is immediate and tremendous when you turn off the engines,” Howie adds. “Our system also reduces collisions because we follow a track as we move aircraft to the terminal.”

The ATS system also reduces engine maintenance intervals because pilots shut off aircraft engines on the ground.

“This provides a trickle-down savings,” he says.

A Better Way to Taxi

The system is the longtime dream of Polish businessman and entrepreneur Stan Malicki, ATS president. Malicki turned to Howie to help develop the concept after a pilot friend expressed frustration about the lengthy taxi times and the needless burning of aviation fuel. Helicopter engineers who worked for Malicki in Poland created the concept then patented it globally.

Malicki turned to Howie to help bring his concept to life. At the time, Howie worked as director of aerospace and defense for the State of Oklahoma, where he recruited aerospace companies to the state.

Oklahoma’s strong aerospace background and pro-aviation business environment encouraged Malicki to eventually move his company there. In 2016, Malicki moved ATS from Poland to Oklahoma and Howie left his state job to become part owner.

“We had completed design work and needed to create a prototype so people could see our concept in action,” Howie explains. “We worked with the Oklahoma State University New Product Development Center (OSU NPDC) in Stillwater, Okla., to design and develop the ATS system prototype. And we brought in experts to create parts of the system.”

Building a Prototype

COVID-19 struck as ATS started work on its prototype. The situation delayed the project for almost a year. But ATS finally broke ground on Jan. 14, 2021 to build a prototype at Ardmore Industrial Airpark.

ATS hired Citadel Construction and several Oklahoma subcontractors to build the underground channel. Eyestone Steel Erectors will erect, assemble and install the unique structural steel components imported from Poland. 4G Concrete Inc. is providing the cement, rebar, mesh and other concrete related materials needed to reinforce the poured-in-place concrete channel. Steel plates will cover the entire underground channel system.

The system’s modular design allows construction crews to install precast sections after hours. The installed sections become operational at once.

“This keeps the disruption to airports minimal,” he says.

Once complete, ATS will use an electric-powered underground pull cart and above-ground tow dolly to run along the U-shaped channel to move aircraft to and from airport runways and gates without relying on aircraft engines. A 400-horsepower Borg Warner electric motor, used in electric cars, powers the pull cart and tow dolly.

ATS purchased a 727 to demo its towing innovation.

“Once complete and weather permitting, we will use the ATS channel to test our aircraft towing system prototype this summer,” he says.

How the ATS System Works

Howie describes the ATS system as a modern rail system for aircraft. The pull cart sits on a track on a monorail in the channel's bottom, which sits underground. Two sets of hydraulic motors, one in front and one in back, move the cart.

Upon landing an aircraft, pilots’ taxi to the correct taxiway and drive the aircraft nose wheel onto the ATS tow dolly, which looks like a round disc with ramps on each end. Doing so secures the aircraft in place.

“Once that happens, pilots turn off the main engines and the tow dolly does the work,” Howie says. “A round tow dolly puts no stress on nose landing gear. There is positive control of the aircraft. The system can pull or push aircraft in different directions, but the pilot maintains control.”

The system works with a foot of snow or an inch of ice.

“Our system eliminates aircraft sliding off taxiways because of the weather,” he says. “And we can program the system to slow down or speed up taxi times. We’re taking this manual system and automating it. OSU calculations show our system will increase throughput in airports up to 30%, without adding a gate.”

He adds airports have asked about using the system for pushbacks. The ATS system would push aircraft away from airport gates with specialized pushcars that also operate in an underground channel.

By designing a system for taxiing and pushbacks, Howie explains, ATS expanded the product’s reach.

“We had targeted 34 airports in the United States for the total system; hubs like Dallas or O’Hare and places like that,” he says. “But we had 22 smaller airports say they needed an electric pushback system, so we developed a curve that lets us bring in an aircraft and flip it as we push it back. Around 200 U.S. airports could benefit from the pushback system.”

The system uses full-size pull cars able to handle regional-size jets up to an A380.

“We sized it to be one size fits all,” Howie says. “In the future, we’ll develop more sizes. Some airports will never have an A380 or 787 and don’t need a bigger size. We are already designing smaller pieces.”

Working with ATS

According to ATS officials, the company has received interest from several major airports across the United States and Europe, including London Heathrow as well as airports in Denmark, Sweden, Dubai, Poland and others.

Should airports decide to add the ATS system, the first step is to simulate the airport.

“We are working on a simulation model right now, so that we can take the airport layout and traffic patterns and optimize them,” he says. “This process determines where we will place track. Power is not an issue—airports have plenty of power. But we need to pay attention to drainage systems.”

The next step is to develop a construction schedule that minimizes downtime.

“We work out a timeline that will cause the least disruption,” he says.

A large airport can expect the project to take 10 to 12 months, while a project at a smaller airport might be complete in 6 months.

“We believe the ATS system will revolutionize the way airports operate and will change the world one airport at a time,” Howie says.